The history and culture of dragonboating

The use of dragon boats for racing and dragons are believed by modern scholars, sinologists and anthropologists to have originated in southern central China more than 2,500 years ago, along the banks of such iconic rivers as the Chang Jiang, also known as Yangtze (that is, during the same era when the games of ancient Greece were being established at Olympia). Dragon boat racing as the basis for annual water rituals and festival celebrations, and for the traditional veneration of the Asian dragon water deity, has been practiced continuously since this period. The celebration is an important part of ancient agricultural Chinese society, celebrating the summer harvest. They first used a "dragon boat" to save a local scholar from drowning in the river and went to save his life. They now honour this feat on (or around) the 5/5 every year (Lunar Calendar).

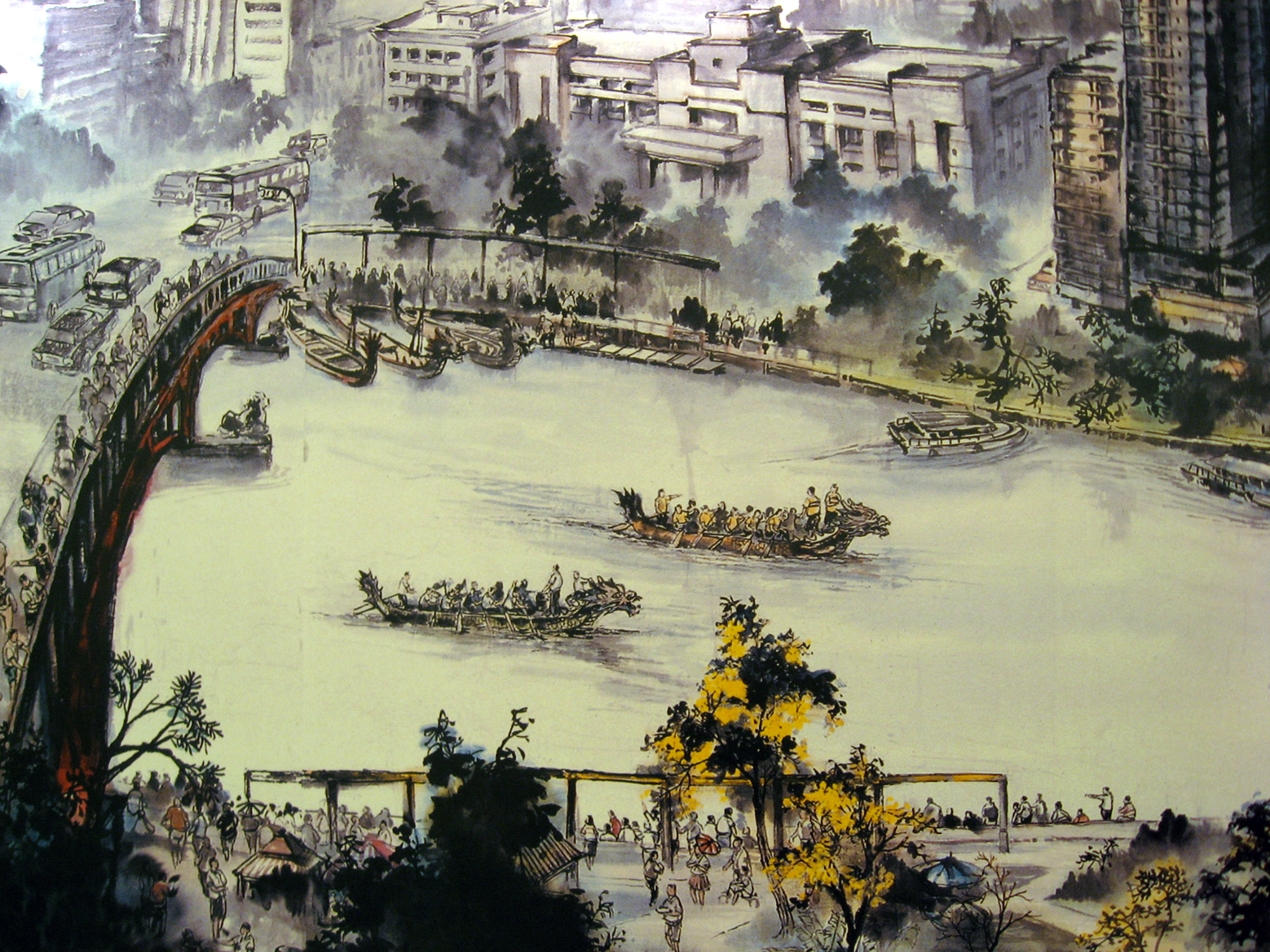

Traditional Chinese dragon boats during the annual dragon boat festival

The heavenly or celestial dragon

The dragon plays the most venerated role within the Chinese mythological tradition. For example, of the 12 animals of the Chinese Zodiac the only mythical creature is the dragon. The rest are not mythical (eg. dog, rat, tiger, horse, snake, rabbit, rooster, monkey, sheep, ox, pig - all of which are familiar to agrarian peasants.) Dragons are traditionally believed to be the rulers of rivers and seas and dominate the clouds and the rains of heaven. There are earth dragons, mountain dragons and sky or celestial dragons (Tian Long) in Chinese tradition.

It is believed sacrifices, sometimes human, were involved in the earliest boat racing rituals. During these ancient times, violent clashes between the crew members of the competing boats involved throwing stones and striking each other with bamboo stalks. Originally, paddlers or even an entire team falling into the water could receive no assistance from the onlookers as their misfortune was considered to be the will of the Dragon Deity which could not be interfered with. Those boaters who drowned were thought to have been sacrificed. That Qu Yuan sacrificed himself in protest through drowning speaks to this early notion.

Dragon boat racing traditionally coincides with the 5th day of the 5th Chinese lunar month (varying from late May to June on the modern Gregorian Calendar). The Summer Solstice occurs around June 21 and is the reason why Chinese refer to their festival as "Duan Wu". Both the sun and the dragon are considered to be male. (The moon and the mythical phoenix are considered to be female.) The sun and the dragon are at their most potent during this time of the year, so cause for observing this through ritual celebrations such as dragon boat racing. It is also the time of farming year when rice seedlings must be transplanted in their paddy fields, for wet rice cultivation to take place.

This season is also associated with pestilence and disease, so is considered as a period of evil due to the high summer temperatures which can lead to rot and putrification in primitive societies lacking modern refrigeration and sanitation facilities. One custom involves cutting shapes of the five poisonous or venomous animals out of red paper, so as to ward off these evils. The paper snakes, centipedes, scorpions, lizards and toads - those that supposedly lured "evil spirits" - where sometimes placed in the mouths of the carved wooden dragons.

Venerating the Dragon deity was meant to avert misfortune and calamity and encourage rainfall which is needed for the fertility of the crops and thus for the prosperity of an agrarian way of life. Celestial dragons were the controllers of the rain, the Monsoon winds and the clouds. The Emperor was "The Dragon" or the "Son of Heaven", and Chinese people refer to themselves as "dragons" because of its spirit of strength and vitality. Unlike the dragons in European mythology which are considered to be evil and demonic, Asian dragons are regarded as wholesome and beneficent, and thus worthy of veneration, not slaying.

Another ritual called Awakening of the Dragon involves a Daoist priest dotting the bulging eyes of the carved dragon head attached to the boat, in the sense of ending its slumber and re-energizing its spirit or qi (pronounced: chee). At festivals today, a VIP can be invited to step forward to touch the eyes on a dragon boat head with a brush dipped in red paint in order to reanimate the creature's bold spirit for hearty racing.

Qu Yuan

The other main legend concerns the poignant saga of a famous Chinese patriot poet named Qu Yuan, also known as Ch'u Yuen. It is said that he lived in the pre-imperial Warring States period (475-221 BC). During this time the area today known as central China was divided into seven main states or kingdoms battling among themselves for supremacy with unprecedented heights of military intrigue. This was at the conclusion of the Zhou (Chou) Dynasty period, which is regarded as China's classical age during which Kongzi (Confucius) lived. Also, the author Sunzi (Sun Tzu) is said to have written his famous classic on military strategy The Art of War during this era.

Qu Yuan is popularly regarded as a minister in one of the Warring State governments, the southern state of Chu (present day Hunan and Hubei provinces), a champion of political loyalty and integrity, and eager to maintain the Chu state's autonomy and hegenomy. Formerly, it was believed that the Chu king fell under the influence of other corrupt, jealous ministers who slandered Qu Yuan as 'a sting in flesh', and therefore the fooled king banished Qu, his most loyal counsellor.

In Qu's exile, so goes the legend, he supposedly produced some of the greatest early poetry in Chinese literature expressing his fervent love for his state and his deepest concern for its future. The collection of odes are known as the Chuci or "Songs of the South (Chu)". His most well known verses are the rhapsodic Li Sao or "Lament" and the fantastic Tien Wen or "Heavenly Questions".

In the year 278 B.C., upon learning of the upcoming devastation of his state from invasion by a neighbouring Warring State (Qin in particular), Qu is said to have waded into the Miluo river in today's Hunan Province holding a great rock in order to commit ritual suicide as a form of protest against the corruption of the era. The Qin or Chin kingdom eventually conquered all of the other states and unified them into the first Chinese empire. The word China derives from Chin.

The common people, upon learning of his suicide, rushed out on the water in their fishing boats to the middle of the river and tried desperatedly to save Qu Yuan. They beat drums and splashed the water with their paddles in order to keep the fish and evil spirits from his body. Later on, they scattered rice into the water to prevent him from suffering hunger. Another belief is that the people scattered rice to feed the fish, in order to prevent the fishes from devouring the poet's body.

However, late one night, the spirit of Qu Yuan appeared before his friends and told them that the rice meant for him was being intercepted by a huge river dragon. He asked his friends to wrap their rice into three-cornered silk packages to ward off the dragon. This has been a traditional food ever since known as zongzi or sticky rice wrapped in leaves, although they are wrapped in leaves instead of silk. In commemoration of Qu Yuan it is said, people hold dragon boat races annually on the day of his death.

Today, dragon boat festivals continue to be celebrated around the world with dragon boat racing, although such events are still culturally associated with the traditional Chinese Tuen Ng Festival in Hong Kong (Cantonese Chinese dialect) or Duan Wu festival in south central mainland China (Mandarin Chinese dialect).